How to use third-party images in your paper

By Pierre Dragicevic, April 2022.

Third-party images are great to illustrate an academic paper, especially if it discusses previous work a lot. Can you imagine how boring it would be to read this paper or this paper without any third-party image? Yet few academic papers include third-party images. Perhaps one reason is that many authors think they're not allowed to do it, or they don't know how to do it. This page is here to provide guidance, mostly to students.

What third-party images can I use in my paper?

This section reflects my current understanding and is by no means authoritative. Please email me if you find an error.

Using third-party images as standalone figures

You can include as a figure:

- Any image that is in the public domain or under a public-domain-equivalent license such as Creative Commons CC0. In principle you can use those images as you wish and without attribution, i.e., without mentioning the author or where you found them. However, in an academic context, the general expectation is that you give credit to authors and link to sources whenever you can. It is also better to explicitly mention that the image is in the public domain so that reviewers and readers know you have the right to use it. We will see concrete examples later on.

- Any image under a Creative Commons license without the mention NC (CC BY, CC BY-SA, or CC BY-ND). The letters NC mean NonCommercial - it is a more complicated case which we will cover next. Note that all CC licenses come with conditions: you cannot include an image unless you meet those conditions. The mention BY requires that you credit the author, which is something you should do anyway, as we saw before. The mention ND (NoDerivatives) requires that you don't change the image, while the mention SA (ShareAlike) requires that if you change it, you should share your version under the same license. If you don't change the image and simply include it as a figure, you can ignore the mentions ND and SA.

- Any image under a Creative Commons license with the mention NC (CC BY-NC, CC BY-NC-SA, or CC BY-NC-ND), with the author's permission. Even if you don't make money with your article, your publisher (ACM, IEEE,...) does. So you're at best in a gray area and it's preferable to have the author's explicit permission. We'll see later how to ask for permission. Authors using NC licenses are usually happy to give their permission if it's for a research paper, so don't refrain from using a nice image just because it says NC. As with the category above, you need to meet the other conditions if specified: attribution, share-alike, no derivative.

- Any copyrighted image, with the author's permission. If there's the © sign, it's clearly copyrighted. But even if you don't see this sign and you can't find a license, you should

assume it's copyrighted. If there is an explicit © mention, consider putting it in your figure caption. Some image authors explicitly ask for this mention to appear.

- Images from other academic papers, with the author's permission. If you wish to follow rules to the letter it's much more complicated than that, because most academic publishers (ACM, IEEE,...) ask authors to sign a so-called "copyright transfer" form where they basically renounce copyright to their images. So formally, reusing an image from a published paper often requires sending a request to the publisher and typically paying money, sometimes even if the image is from a paper you wrote. I (and other researchers) consider this practice unacceptable, and so I just ignore copyright transfer and directly ask permission to authors. Although I can't imagine any author would complain if their paper is cited and the figure caption explicitly indicates that the image was taken from their paper, I prefer to get explicit permission to cover my back ; I think it will be hard for a publisher to do anything against me if the author from whom they stole the image gave me their permission. Also, when I ask for permission, I ask the author if they have a similar image or another version they didn't include in their paper, in which case the copyright transfer doesn't apply.

- There are many other cases, depending on the image license. Generally look at the conditions under which your are permitted to reuse the image, and make sure you fulfill those conditions. If you find licenses too complicated to understand, just stick to the known cases above.

Using third-party images in my own image

You might want to use third-party images not as standalone figures, but as raw material for creating your own image, and then include your own image as a figure. For example, you might want to use clipart taken from the Internet in your own diagram. What you're allowed to do is similar to the standalone figure case, but with differences:

- All third-party images that you have reused and that require attribution (e.g., images with a CC BY license) need to be properly credited, e.g., in your figure caption. However, in my opinion, you generally don't need to source these images. For example, if you use simple cliparts or symbols, adding links to where you found those images would take up space and would be of little interest to readers. In addition, if you use images where attribution is not required (i.e., public domain or equivalent), it's generally OK not to credit the authors, especially if those are very simple images. Exceptions include cases where most of your image consists of a third-party image (e.g., you reuse a nice photo of a landscape and just add text on top of it, in which case it is nicer to credit the photo author), and cases where you reuse images that present an academic interest (e.g., you reuse a photo of a novel interactive system, in which case you should source the image or cite the paper).

- You cannot use Creative Common images with a mention ND (NoDerivatives). But you can still use other CC licenses which don't have the ND mention.

- If you use a Creative Common image with a mention SA (ShareAlike), you will have to share your image with the same license. You can do this by specifying the license of your own image in your figure caption.

- For images for which you need author permission (e.g., copyrighted images), you need to send your own image to the author to explain to them what you will do exactly with their image.

Clearly, using anything else than public-domain images in your own image is complicated. So I recommend you first search for public domain images whenever you need clipart or photos to create your own image.

Where do I search for public domain images?

Here are four good options:

- Flickr. Make sure the license remains set to "No known copyright restrictions" in the search bar.

- Unsplash. The Unsplash license is a a public-domain-equivalent license.

- Wikimedia commons. Make sure the license remains set to "No restrictions" in the search bar.

- Pexels. The Pexel license is a public-domain-equivalent license.

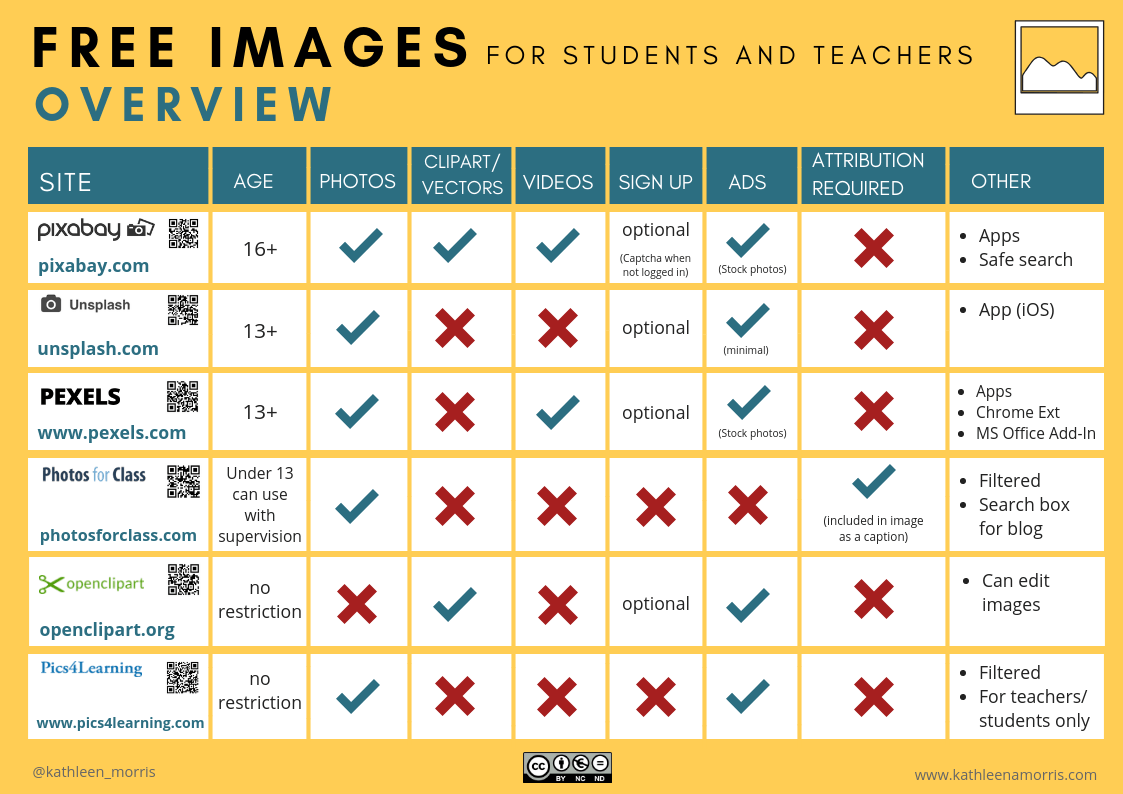

Other options are listed in the blog post 31 free public domain image websites.

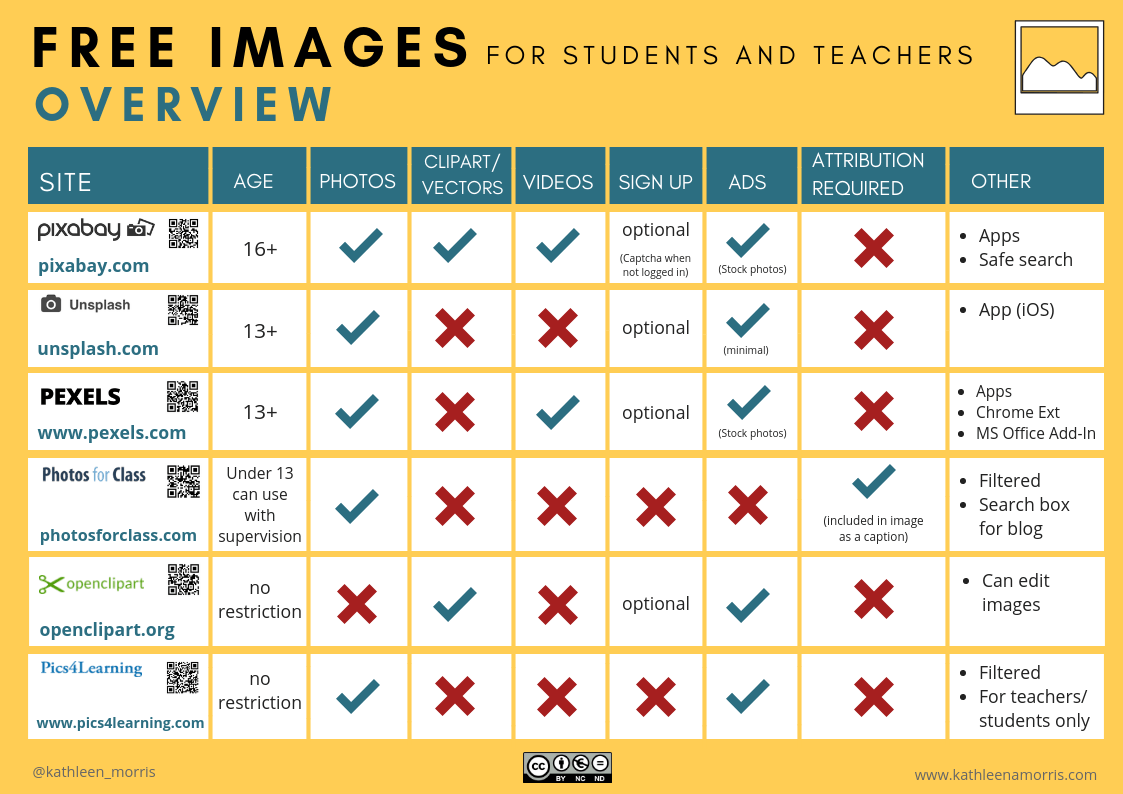

Here is also a nice cheat sheet by Kathleen Morris, although I'm told it might not be up-to-date:

How do I give credit in my paper?

There is no commonly accepted standard for this, but the figure caption is by far the most common place for this type of information and it should contain at least partial credit information. Complementary information can be provided in the paper's text, in a footnote, or in the bibliography. See the examples below.

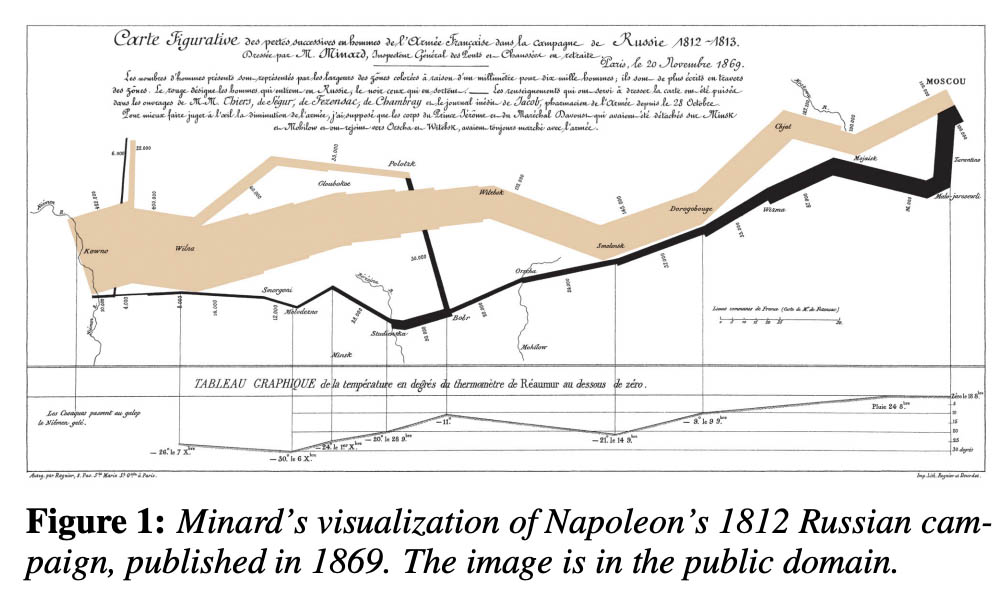

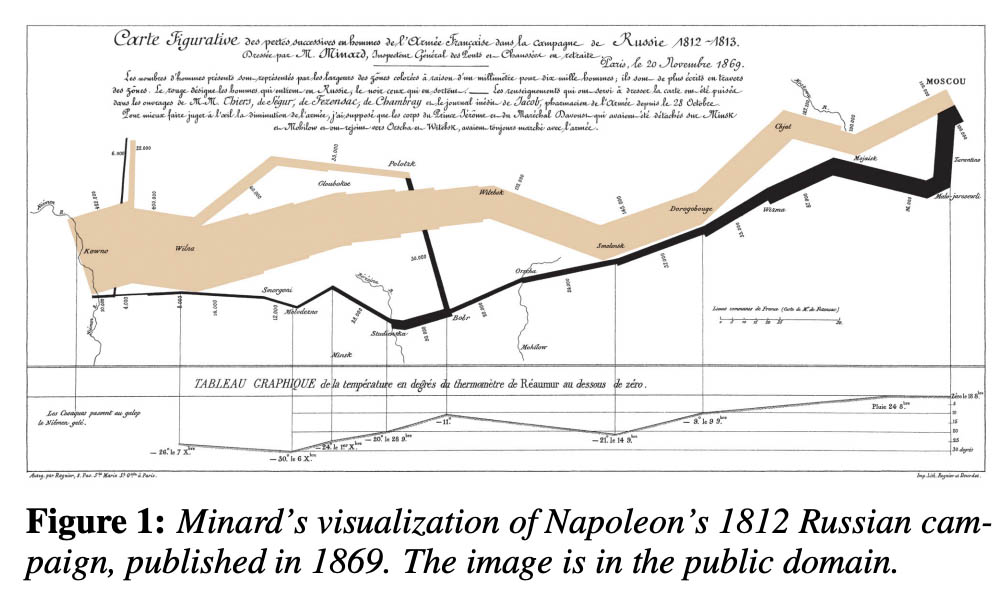

Example 1

Above is an imperfect example of how to credit a public domain image, taken from this paper. The figure caption mentions the author's last name and states that the image is in the public domain – This is good, but it would have been preferable if it also included a full citation to the book where the image was published and a URL to help readers find the image.

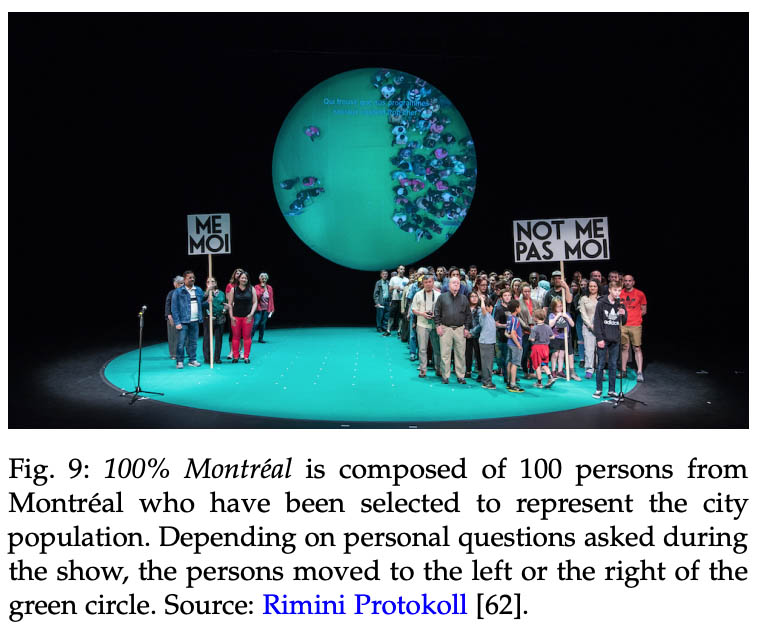

Example 2

Bibliography entry:

Bibtex:

@misc{haug2015100,

author = {Haug, Helgard and Kaegi, Stefan and Wetzel, Daniel},

title = {{100\% Montréal}},

howpublished = "\url{https://www.rimini-protokoll.de/website/en/project/100-montreal}",

year = {2015},

note = "[Online; accessed 14-February-2020]"

}

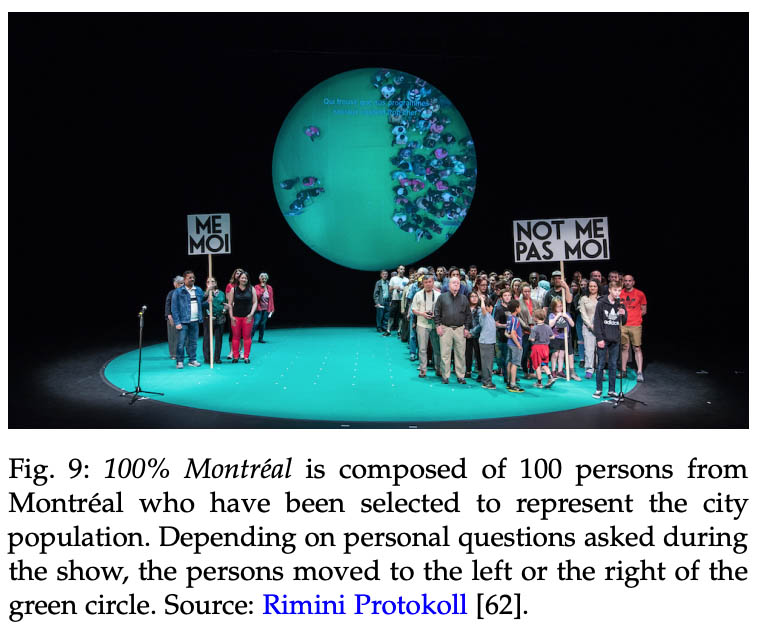

Above is an example taken from this paper. The author names don't appear in the figure caption, but a citation to a web page is provided instead, with full author list in the bibliography. Both approaches are OK, but be consistent across your paper. The figure caption also links to the web page the image was taken from. This is optional but can be very convenient for the reader. Note that the captions doesn't display the full URL because it would have taken a lot of space and it would have been useless since people can click on the link, and when reading paper print-outs, few people bother copying long URLs. However, clicking the link does open the full URL. Always link directly to the page where the image can be found, and never provide a link that makes it hard for the reader to find the image.

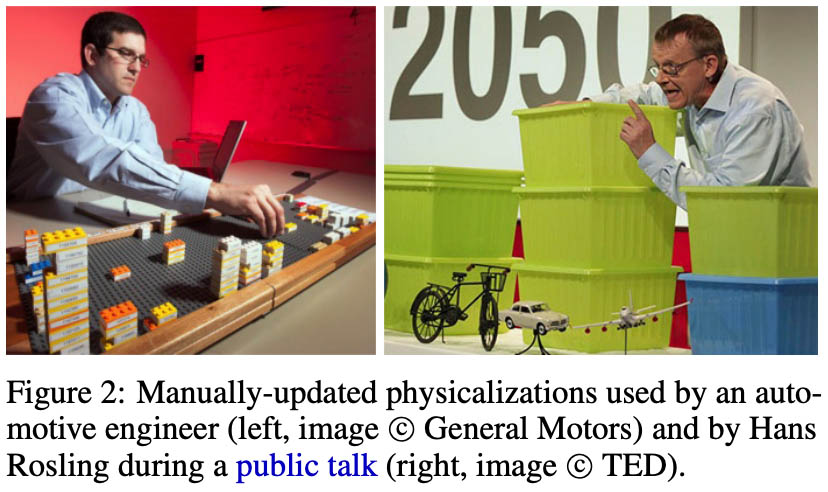

Example 3

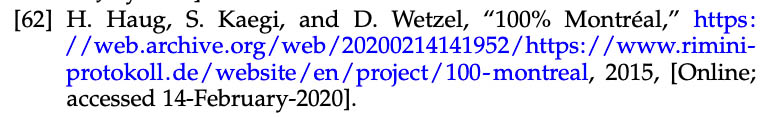

In the paper's text:

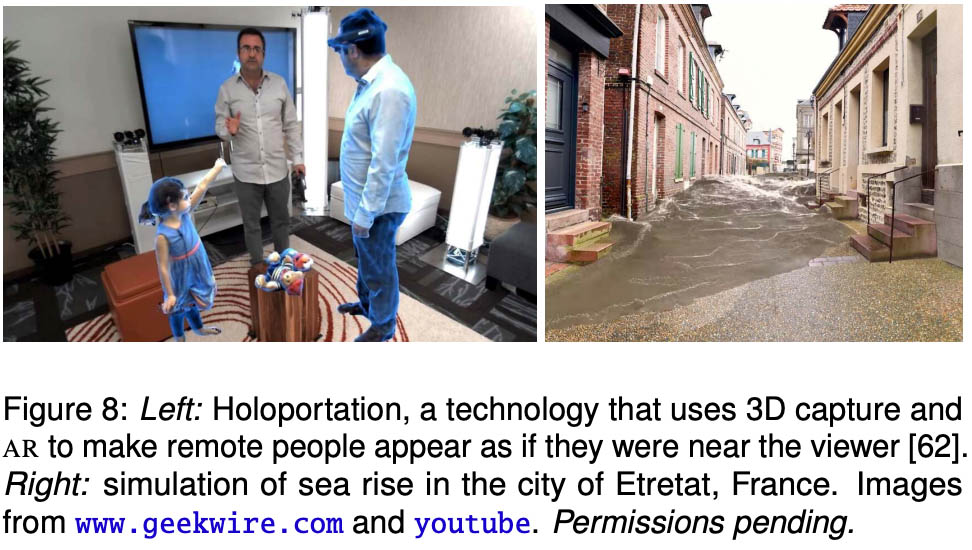

Above is another example, taken from this paper. In this case, copyright mentions have been included at the authors' request. The caption has only partial information: it does not use full citations and only one hyperlink is provided, but the text describing the images contains a link to a web page for each of the two images. The links are in the text itself, but they are also often given as footnotes, and sometimes as full citations. Again, just be consistent across your paper. Perhaps avoid URL shorteners like in this example, because those services might go offline one day.

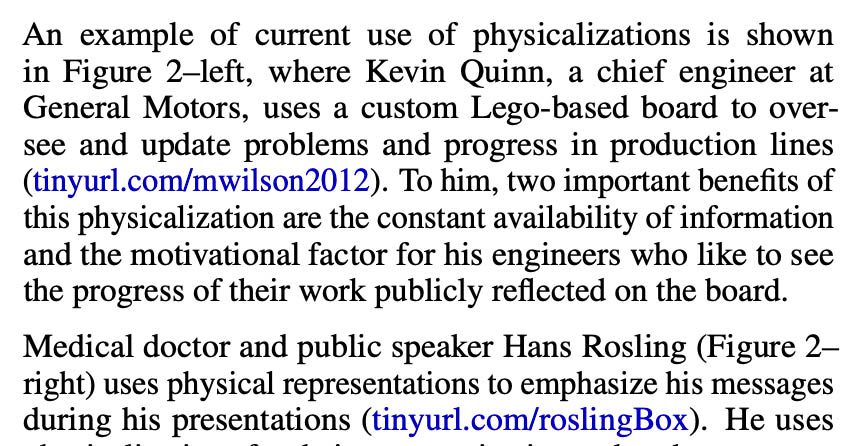

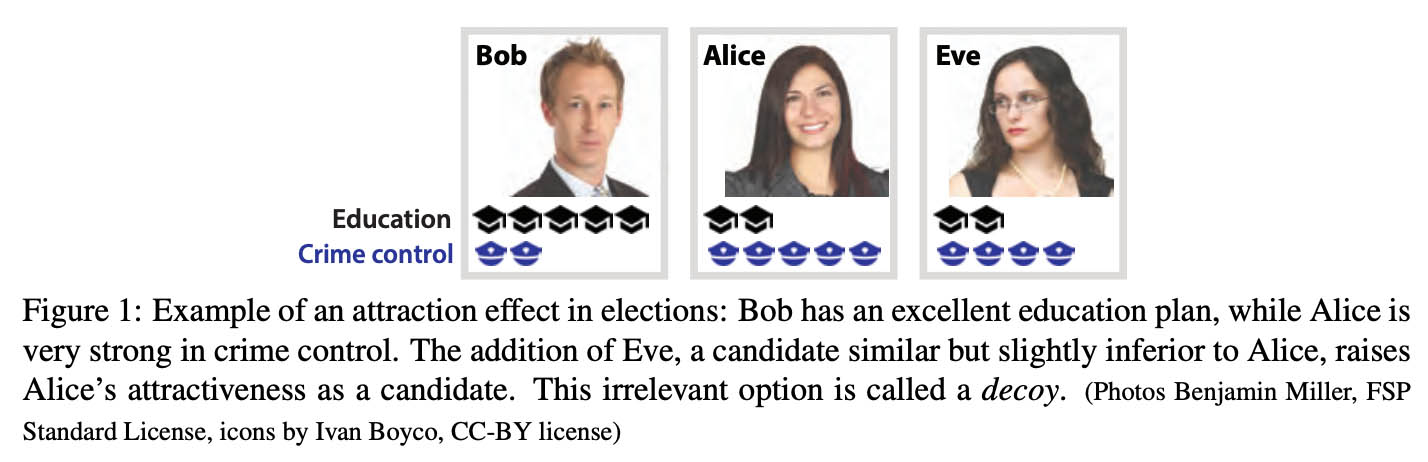

Example 4

The example above is taken from this paper. The image shows a system previously described in an academic paper, so the caption simply cites that paper. However, the specific image used here is not in the cited paper and was taken from somewhere else (possibly a web site, or directly provided by the author). This is better than taking images directly from the paper as it circumvents copyright transfer issues. However, there is no information here on where to find this image, so the caption can be improved.

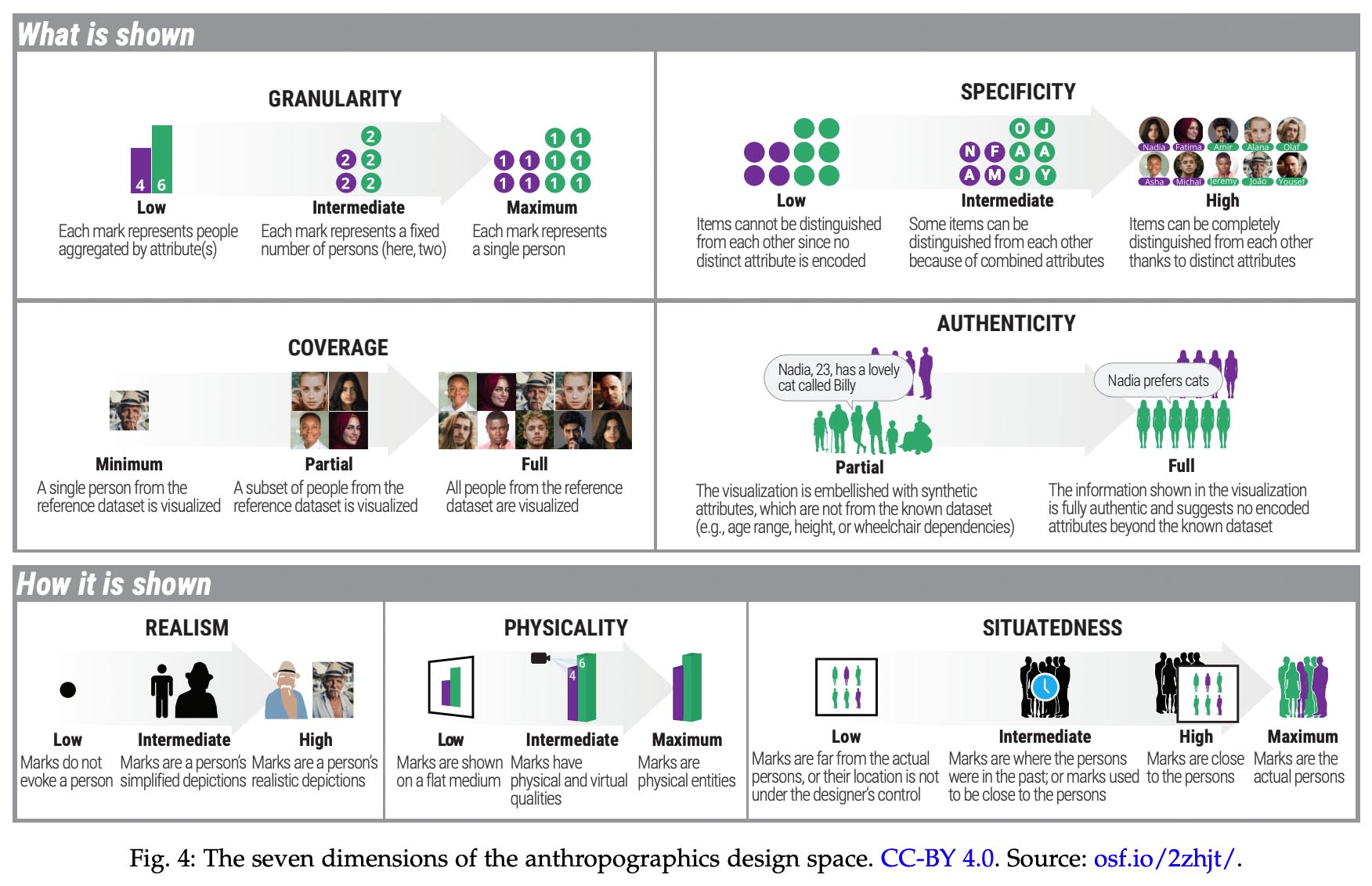

Example 5

Above is an example of derivative work, taken from this paper. The authors used existing photos and icons to build their own image. Since both the photos and the icons require attribution, the figure caption acknowledges both authors.

Example 6

This other example of derivative work, taken from this paper, only uses photos and icons in the public domain or with public-domain-equivalent licenses. Therefore, acknowledging the authors and linking to the image sources is not necessary. However, the caption specifies that the entire image is under CC BY and links to a higher-resolution version, so that the image can be freely reused by other authors and is not covered by the copyright transfer to the publisher. You can do this for example if you reuse images under a Creative Common license with a mention SA (ShareAlike).

Those examples are not exhaustive. Some papers also add the mention "used with permission" to captions of copyrighted images. It's OK to do this, although it is somehow self-evident that all images requiring permission are used with permission.

What to do while writing your paper

While you're in the process of writing your research paper to submit to a journal or a conference, you should feel free to reuse third-party images, but remember to credit and source them as explained before. Do it as you go and don't wait for the last minute, because you might forget where the images come from. Nevertheless, you shouldn't be overly worried about image license and permissions at this stage, i.e., when you submit your paper for peer review.

Reasons not to care:

- Papers you submit for peer review are considered confidential. Therefore, it is legally OK to include images without permission at this stage, because you're not sharing your paper publicly.

- As we saw, third-party images are great to illutrate a paper but few people use them, partly because it is too much work. So not worrying too much about the licences and permissions of third-party images at first can reduce friction and make it more likely that your paper will include nice third-party images.

Reasons to care:

- It's worth caring a bit about image license and permission early on, because you can save time later. For example, if you need a photo to illustrate a concept and you pick the first result you like on Google Images, chances are that this photo is copyrighted and that getting permission for it will be difficult or impossible. You will therefore need to find another photo. But if you spend a little bit of extra effort searching for a public domain photo instead, you won't have to worry about it later. This is especially true if you're making an image that uses third-party photos or clipart: if you don't pay attention to licenses, you might have to redo your figure.

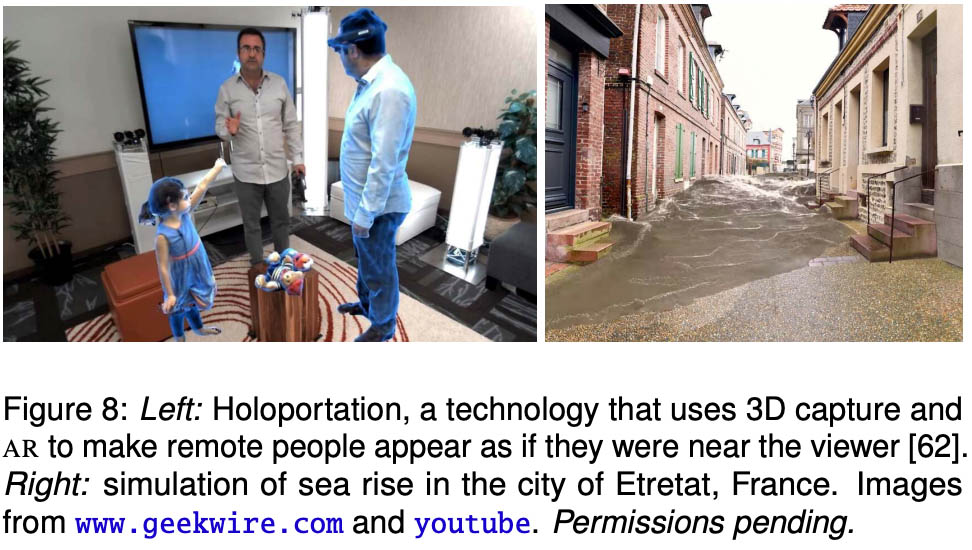

- If after your paper is accepted you need to remove or replace many images because you can't get permission for them, the final paper will differ a lot from the original submission. Therefore, trying to find images that are likely to remain in the final revision is more honest to your reviewers. For the same reason, it is always preferable to add the mention "Image permission pending" or "Permission pending" to the caption of all images for which you need to ask permission. That way your reviewers will know that those images might not be there at the end. Example here, from the submitted version of this paper:

Your likelihood of eventually obtaining image permission depends on whom you ask. From my experience:

- Researchers will almost always grant you permission, because they love when a paper talks about their work. You might need to send one or two reminders.

- Casual photographers (e.g., regular people posting photos on their web page or Flickr) are often happy to grant permission.

- Designers, artists and companies are often happy to let you use images of their work to get more exposure, unless they're already famous.

- Famous artists have an agent who likely won't give you permission for free. Even when it's not expensive, the process seems very complicated.

- Newspapers and magazines are very unlikely to give you permission for free, and their process also seems complicated.

- Professional photographers will never give you permission for free, because selling photographs is how they earn their living.

What to do after you submitted your paper

Don't wait to receive your reviews to start asking for image permissions. Getting permissions can take a long time: many people are slow at responding or need reminders, and if someone never replies or says no, you will need to find a new image and you're back to square one. One or two weeks after submission is a good time to start.

One issue to consider, however, is that asking for permission early on can break author anonymity. In particular, if you ask permission for an image that is taken from a paper, it is not inconceivable that the person to whom you're asking permission has been asked to review your submission. If your venue allows for non-anonymous submissions (e.g., IEEE VIS) this is fine, but if it requires authors to be anonymous, the consequences are hard to predict. Paper chairs and editors are more or less strict about anonymity depending on the venue and on the year, and different reviewers will react in different ways as well. This can (in rare cases I think) result in your paper being rejected. If you're worried about this, it makes sense to ask permission for images taken from papers after you receive the final notification of acceptance, especially since we saw that researchers are most of the time happy to give permission.

Two tools are very useful for requesting image permissions: a spreadsheet and email templates. If you have many third-party images, those are mandatory if you don't want to become insane.

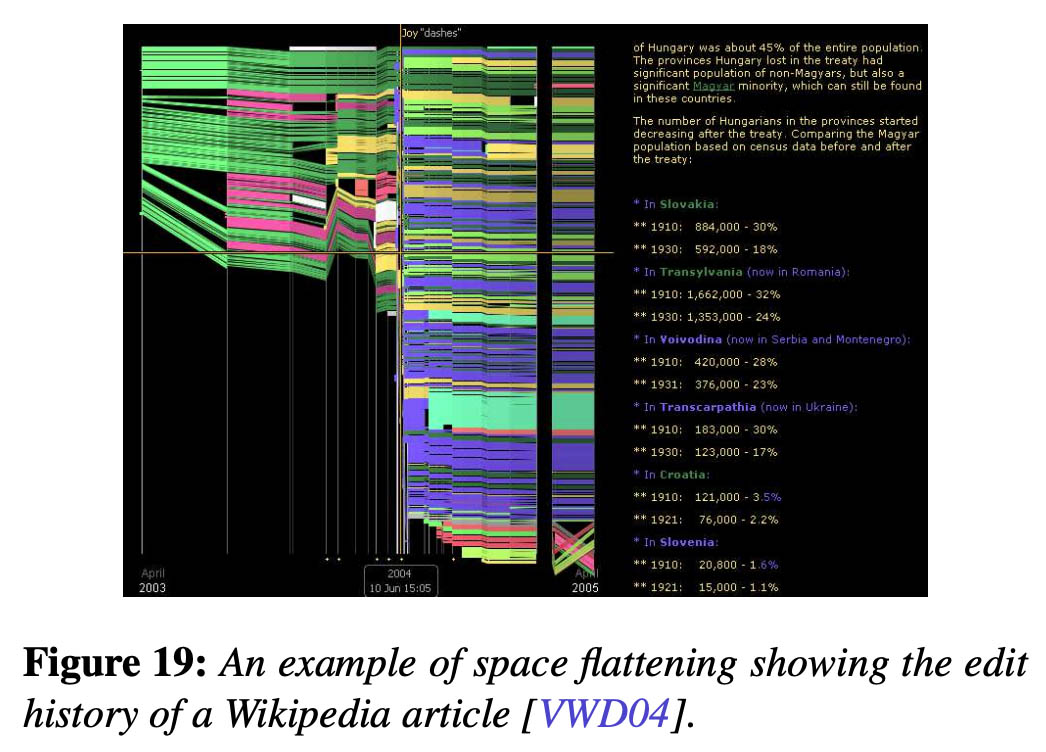

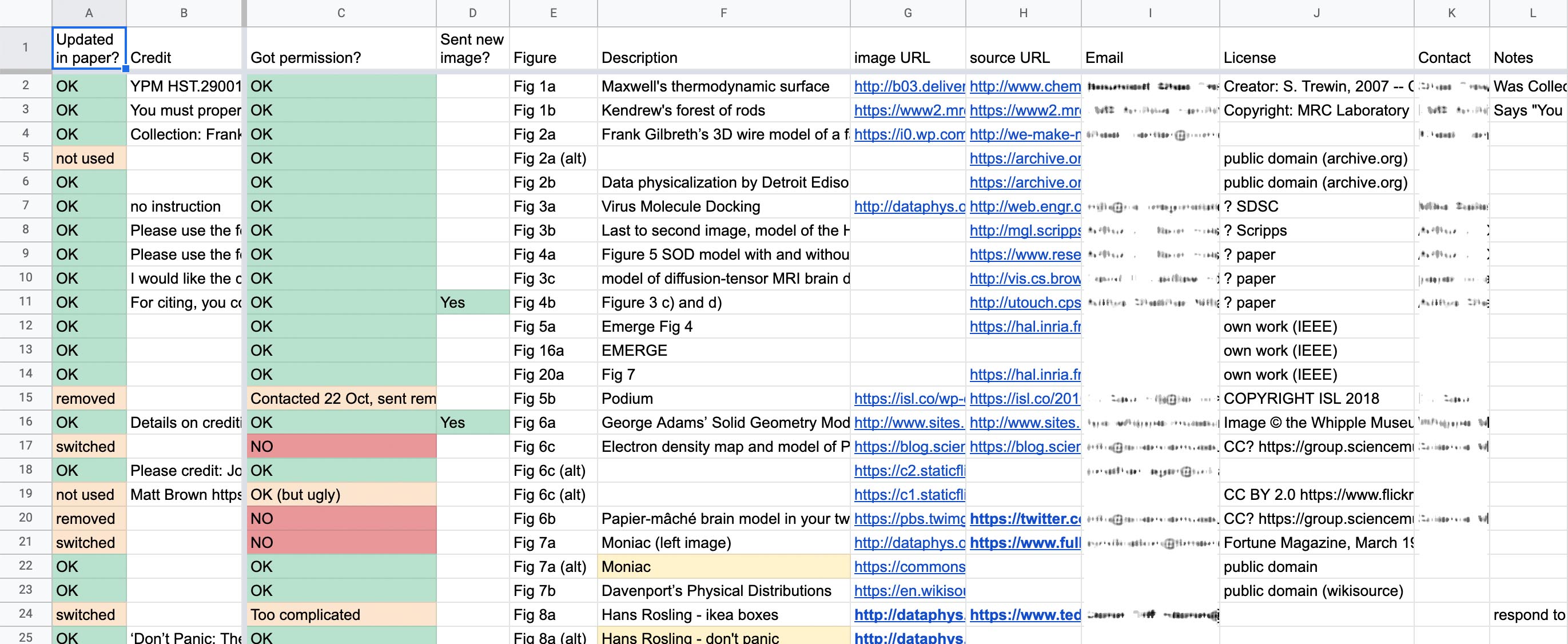

The spreadsheet

The first thing to do is to create a spreadsheet that lists all the third-party images you're using in your paper, along with extra information and permission status. Here is an example (click for full-res image):

This was for a 50-page survey, so it has many images listed (68 rows in total!). But this kind of spreadsheet is also useful if you only have 3 images. On this example, I started filling columns E (Figure number in my paper), F (short description), G (URL directly pointing to the source image, if available), H (URL pointing to the web page that has the source image), I (email of a person to contact, usually found on that web page), J (image license as stated on the web page), and K (name of the person or company to contact).

Columns A to D will be filled later. I suggest you go row by row: find the image in your paper, go to the website where you found it, and gather all information necessary to fill the spreadsheet columns. Finding a contact email is often the most time-consuming: sometimes you'll need to follow multiple links, google somebody's name, or even connect to people through social networks to reach them. If you can't find an e-mail and the image requires permission, find a replacement immediately.

A template for this spreadsheet is available online as a Google spreadsheet. Open the Google spreadsheet then copy it (File menu, Make a copy), and it's yours.

The email templates

Next step, write an email template in a document editor. You will probably have to do slightly different versions depending on whom you're talking to. Here is an example of an email template for a image you found on the web:

Template 1 (image on the web)

Email title: Permission to use your image in an academic article

Dear John,

We are requesting permission to use the image below in an academic article entitled "Immersive Humanitarian Visualization".

The image we would like to use is this one:

[copy image]

We downloaded it from http://www..... (direct image link: http://www.....).

You can find a current draft of our article here: http://www.... Your image appears in page 8. Please do not share this PDF, as the article is still under review. If accepted, our article will be published by IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers) in the TVCG journal, and presented at the VIS 2022 conference.

If you agree, we will credit your work by adding the text "Credit John Doe and Mary Jane" to our figure caption.

Please let us know, if possible within the next two weeks:

1) If you give us permission to use your image as described,

2) If you would like us to change the way we credit your work.

If positive, your reply to this e-mail will be submitted to IEEE as a proof that we got your permission to include your work. If you don't control these rights, please let us know to whom this request should be directed.

If we don't hear from you, we will remove your image from our article.

Best regards,

Pierre Dragicevic and Catherine Cayla

Inria Bordeaux and CNRS

And here is an example of permission request template for academics:

Template 2 (image in a paper)

Email title: Permission to use your image in an article

Dear John,

We are requesting permission to use the image below in an article entitled "Immersive Humanitarian Visualization".

The image we would like to use is a cropped version of Fig 5.3 in your article available at https://www...paper_url.pdf:

[copy image]

You can find a current draft of our article here: http://www.... Your image is shown on page 8. Please do not share this PDF, as the article is still under review. If accepted, our article will be published by IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers) in the TVCG journal, and presented at the VIS 2022 conference.

If you agree, we will credit your work by adding a citation to your paper in our figure caption.

Please let us know, if possible within the next two weeks:

1) If you give us permission to use your image as described,

2) If you would like us to change the way we credit your work,

3) If you can send us a higher-resolution or an alternative version of your image. We would really appreciate an alternative version that is not used in your publication, such that we are sure we are allowed to use it.

If positive, your reply to this e-mail will be submitted to IEEE as a proof that we got your permission to include your work. If you don't control these rights, please let us know to whom this request should be directed.

If we don't hear from you, we will remove your image from our article.

Best regards,

Pierre Dragicevic and Catherine Cayla

Inria Bordeaux and CNRS

The differences with the previous template are the following:

- "The image we would like to use is a cropped version of Fig 5.3...": instead of linking to a web page, the template links to a published paper and gives a figure number.

- There is an important third request that asks for a high-res image (figures in PDFs are often low-res) and/or an alternative image (recall it's always better to use an alternative image).

- The default credit consists of simply citing the paper (which most researchers will accept).

- Minor change in wording: "academic article" becomes "article", which is a more common term in academia.

General comments about the two templates:

- I don't know if it's still the case, but ACM used to ask authors of accepted papers to submit a proof that they have permission to use each third-party image. This proof could be a PDF printout of a webpage stating the license of an image, or a PDF printout of the email correspondence between you and the image author. I think IEEE only requires you to sign that you have permission to use all third-party images. In any case, keep the email correspondence between you and the author who gave you permission, as you might have to use it as a proof that you have permission. This also means that while it's OK to use direct messages on Twitter, LinkedIn, etc., to establish contact with an image author, always try to have them give you their email address and have them explicitly give you their permission via e-mail.

- You don't have to include a draft of your article. From the permission requests I've received myself, most people don't. But I prefer to do it. It seems more transparent, and it's never too early to start advertising your article!

- If you're reusing several images from the same author, mention them all in your email. Don't send one email per image.

- The template says you'd like to receive a response within two weeks. Even when you have plenty of time, always give a deadline. Otherwise people might think it's OK if they respond in 6 months. Also remember that if someone says no, you need time to get permission for a replacement image.

- You can use the first person "I" and you don't have to cc all your co-authors on every e-mail, but I recommend you list all co-authors at the end of your email because it is perceived as more polite if you write to a researcher. Researchers often want to know the full list of people involved in a research project.

- It's common courtesy to ask image authors how they would like to be credited exactly (what text to put in the figure caption, what URL,...). It's important you respect their wishes as long as they're reasonable.

- Obviously, you need to adapt the template to your case. For example if you're submitting to UIST, the sentence starting with "if accepted..." could become:

If accepted, our article will be published by ACM (Association for Computing Machinery) in the proceedings of the UIST 2002 conference, and presented at that conference.

Double and triple-check each email before you send it, and don't hesitate to make small adaptations depending on the particular case. For example if you're writing to someone you know, you could start with "I hope you're doing well", etc.

Process

- Go through your spreadsheet row by row, and send email requests one by one. Again, don't rush and verify your emails before you send them (e.g., have you forgotten to update the recipient's name?). Then right after you sent your email, update your spreadsheet. If you use the example spreadsheet, write "Contacted [date]" in column C. Writing the date is useful when you need to decide whether or not to send a reminder.

- Each time your receive an answer, reply to the sender (if only to say thanks) and update your spreadsheet. In my example spreadsheet, this would mean updating column C by putting "OK", "NO", or something else. If the author gives you permission but would like you to change the way you credit them, copy and paste their exact instructions in column B. If they send you an alternative or higher-res image, put that information in column D and save the image somewhere.

- About ten days after you sent your emails (or less if there is not much time left), send a reminder to those who didn't reply. I guess I'm not the best at writing reminders but here's a template I've used in the past:

Dear John,

This is gentle reminder that we would like to feature your work by including an image of yours in our article. If we do not receive a response in the next few days, we will remove your image.

Thanks a lot,

Pierre Dragicevic and Catherine Cayla

Inria Bordeaux and CNRS

Sending reminders is very important, and you should expect to send several of these. Make sure you don't forget (I put this as a do-to item in my calendar or send myself a scheduled e-mail). For those who still don't reply you can send a second reminder, perhaps by cc'ing other co-authors if the image has multiple authors or is from a paper with multiple authors. Sometimes there's just an author who's not responsive, but others will respond. But if you still don't get a response after that, consider you don't have permision.

- If all goes well and your paper is accepted, you will soon be asked to create a camera-ready (i.e., final) version of your paper. This is a stage that takes time whether or not you have third-party images, so make time for that in your calendar. Concerning your third-party images, go again row by row in your spreadsheet and for each figure, update the image and everything else in your paper (credits, links, possibly references). Each time you have updated a figure, write that down in your spreadsheet so you'll remember (column A in my example). Remove the images for which you couldn't secure permission and for which you couldn't find alternatives, and make sure the text remains consistent and doesn't refer to a non-existing figure.

Using third-party images can be a lot of work but think about how delighted the readers of your paper will be with all those nice and useful illustrations.